Graenaland

Graenaland

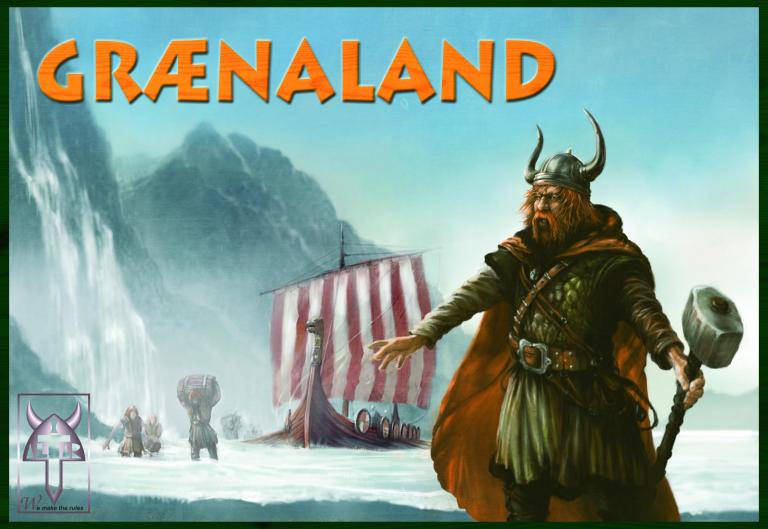

In 982, a Viking jarl called Erik the Red sailed from the western coast of Iceland and discovered a new land. He named it Graenaland, a green land. Four years later the first colonists arrived to Greanaland and founded settlements that lasted more than four centuries.

Take the role of one of the jarls leading their clans to the new home. You have to settle the coast and to agree with your neighbors on how to distribute the spare resources the land is giving away. As Eric wants no fights amongst Vikings, any conflicts are solving by voting. You could improve your position in order to gain more votes; however, you can also try to be righteous and to keep good relations with all your neighbors. Cooperating with them, you can fertilize and improve the land easier than when struggling for influence; just keep your position strong enough for the case something goes wrong.

At first glance, it might remind you just another settler-like game – there are tiles of different terrains, there are villages and other buildings built on the tiles, and there are resources produced to build more of them. However, Graenaland uses these elements by very unusual way, and offers brand new player interaction.

The main difference is that villages produce no resources; the tile produces them. They remain placed next to the tile, until players agree how to distribute them. Every village on the tile gives one vote to its owner, as well as the traveling heroes just visiting the tile – and you need more than half of the votes total for your proposal how to distribute the resources.

A tile produces only one resource per turn, no matter how many villages of how many players is built on it. Building more villages on the same tile strengthens your position here; however, if another player does the same, you both are spending lots of efforts and resources struggling for still the one resource card. May be it would be wise to live in peace instead. If you are able to come to an agreement, you can take turns taking the resource. You can vote together in the case an intruder appears. You can build some improvements on the tile together, increasing its resource production. You can spread your villages to other tiles and let your hero travel where it is more needed, rather than struggling for influence on this tile.

If you trust each other, you can work much more efficiently. However: does your neighbor deserve your trust? What if he returns with his hero unexpectedly, and confiscates the whole harvest of several turns? What if he builds another village here instead of the improvement he promised? And especially – what would you do if you get such an opportunity yourself?

The game mechanics – simultaneous movement of heroes, small anomalies in player roles (one player has special role every turn), and decent randomness and uncertainty in resource harvesting (each terrain produces resources of more types, with different probabilities) lead to enough interesting asymmetric situations, and it is up to you whether you take any advantage you have, or whether you try to appear fair and righteous to the others instead. As the others take it in to account when searching for partners for their deals.

Take the role of one of the jarls leading their clans to the new home. You have to settle the coast and to agree with your neighbors on how to distribute the spare resources the land is giving away. As Eric wants no fights amongst Vikings, any conflicts are solving by voting. You could improve your position in order to gain more votes; however, you can also try to be righteous and to keep good relations with all your neighbors. Cooperating with them, you can fertilize and improve the land easier than when struggling for influence; just keep your position strong enough for the case something goes wrong.

At first glance, it might remind you just another settler-like game – there are tiles of different terrains, there are villages and other buildings built on the tiles, and there are resources produced to build more of them. However, Graenaland uses these elements by very unusual way, and offers brand new player interaction.

The main difference is that villages produce no resources; the tile produces them. They remain placed next to the tile, until players agree how to distribute them. Every village on the tile gives one vote to its owner, as well as the traveling heroes just visiting the tile – and you need more than half of the votes total for your proposal how to distribute the resources.

A tile produces only one resource per turn, no matter how many villages of how many players is built on it. Building more villages on the same tile strengthens your position here; however, if another player does the same, you both are spending lots of efforts and resources struggling for still the one resource card. May be it would be wise to live in peace instead. If you are able to come to an agreement, you can take turns taking the resource. You can vote together in the case an intruder appears. You can build some improvements on the tile together, increasing its resource production. You can spread your villages to other tiles and let your hero travel where it is more needed, rather than struggling for influence on this tile.

If you trust each other, you can work much more efficiently. However: does your neighbor deserve your trust? What if he returns with his hero unexpectedly, and confiscates the whole harvest of several turns? What if he builds another village here instead of the improvement he promised? And especially – what would you do if you get such an opportunity yourself?

The game mechanics – simultaneous movement of heroes, small anomalies in player roles (one player has special role every turn), and decent randomness and uncertainty in resource harvesting (each terrain produces resources of more types, with different probabilities) lead to enough interesting asymmetric situations, and it is up to you whether you take any advantage you have, or whether you try to appear fair and righteous to the others instead. As the others take it in to account when searching for partners for their deals.

Player Count

3

-

5

Playing Time

90

Age

12

Year Released

2006

Podcasts Featuring this Game

TDT # 72: Top Ten Games from Essen 2006

Not so much regular news this week, but we continue our contest for Quest for the Dragonlords. I review Take Stock, and we discuss our Hot Games of the Month. We answer some questions, but the main part of our show is a special report from Rick Thornquist and Moritz Eggert